(RxWiki News) While a high-fiber diet may ease constipation, it might not be a cure for a common colon condition called diverticulosis. In fact, having more bowel movements could worsen the problem.

In patients who have diverticular disease, pouches called diverticula form in the colon. These pockets can trap food and become inflamed, leading to possible infection and bleeding.

For more than 40 years, doctors have suggested that eating fiber-rich meals could help prevent diverticulosis. But a new study shows that the opposite may be true.

"Check with your doctor about alternate treatments for diverticulosis."

Anne Peery, MD, a fellow in the gastroenterology and hepatology division at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) School of Medicine, led research analyzing data on 2,104 patients.

The patients were 30 to 80 years old and underwent outpatient colonoscopy at UNC hospitals from 1998 to 2010.

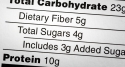

After interviewing individuals about their diet, bowel movements and level of physical activity, doctors concluded that high consumption of fiber did not reduce the prevalence of diverticulosis. Instead, those patients eating the most fiber had the highest incidence of the disease.

"We were surprised to find that a low-fiber diet was not associated with a higher prevalence of asymptomatic diverticulosis," said Dr. Peery, “It looks like we may have been wrong about why diverticula form.”

For years, doctors have thought that increased pressure in the colon caused by constipation created diverticula. But, in this study, constipation did not appear to aggravate the condition.

In fact, patients who had more than 15 bowel movements per week had 70 percent greater risk of diverticulosis compared to those who had fewer than seven bowel movements per week.

The study also reported no connection between diverticulosis and physical inactivity or eating fat and red meat.

About 10 percent of Americans older than 40 have diverticulosis and about half of all people older than 60 have the condition, according to National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institutes of Health.

Based on these results, Dr. Peery and her team suggest these patients may need different diet recommendations, but more research is needed before doctors change their current approach to treatment.

"It’s too early to tell patients what to do differently,” said Dr. Peery, "but figuring out that we don't know something gives us the opportunity to look at disease processes in new ways."

This study was published in the February issue of the journal Gastroenterology. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. There were not conflicts of interest noted.