(RxWiki News) In the late 1990s there was a striking disparity among the number of black children who died of stroke as compared to white children. Black children were 74 percent more likely to die of a stroke, because of the higher prevalence of sickle cell anemia in that population.

Adding preventative strategies including ultrasound screening and chronic blood transfusions have since significantly closed that gap, a new study has found. Between 1999 and 2007, the excess risk dropped by two thirds.

"Seek regular screenings for children with sickle cell anemia."

Dr. Laura Lehman, lead researcher and a clinical fellow in the Cerebrovascular Disorders and Stroke Program in the neurology department at Children’s Hospital Boston, said researchers expected to see a decline in ischemic stroke deaths among black children, but were impressed with how quickly the racial disparity began to narrow.

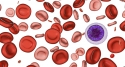

The existing gap in part stems from a higher rate of sickle cell anemia among black children. Sickle cell anemia occurs when red blood cells take on an abnormal crescent shape that have trouble navigating the small capillaries in the circulation.

Researchers reviewed death certificates from the National Center of Health Statistics for all U.S. children under age 20 from 1988 to 2007. They then calculated the relative risk of dying for white and black children.

Investigators found that 20 percent of the 4,425 deaths reviewed during the study occurred as a result of an ischemic stroke. They determined that black children were 27 percent more likely to have ischemic strokes than white children, according to death certificate data for U.S. children who died of ischemic stroke. This was substantially lower than the racial disparity found in 1998.

Researchers attributed the reduced disparity to improvements in sickle cell anemia prevention efforts including ultrasound screenings of the brain and blood transfusions, since they marked the only major changes in pediatric stroke care in the past 20 years. A previous study found that chronic blood transfusions lower stroke risk by 90 percent in children with sickle cell anemia.

Additional research will be needed to determine whether prevention strategies have lowered the number of deaths that occur among black adults with sickle cell anemia. Adults tend to have hemorrhagic strokes instead of ischemic strokes.

The study was recently presented at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference 2012 in New Orleans.