(RxWiki News) Children inherit many things from their mothers. Unfortunately, cancer risk is no different.

That's why researchers from the Mayo Clinic are taking an in-depth look at caring for women with a hereditary risk for breast or ovarian cancer.

Study co-author Lynn Hartmann, MD, said in a press release, "Women whose families have been marked by excess breast and ovarian cancer are at higher risk of developing those diseases over their lifetime. Although these women can reduce their risk considerably through preventive mastectomies and or the removal of their fallopian tubes and ovaries, these procedures come with their own complications and psychosocial effects."

In their report, Dr. Hartmann and co-author Noralane Lindor, MD, provide a thorough look at the complexity of caring for these women. Dr. Hartmann is an oncologist. Dr. Lindor is a pathologist and genetics expert. Both practice at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MI.

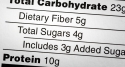

Drs. Hartmann and Lindor noted that more than 200,000 US women are diagnosed with breast cancer each year. That figure is more than 20,000 for ovarian cancer.

New therapies and early diagnosis have improved survival rates, according to Drs. Hartmann and Lindor. Sorting through the options, however, is not an easy task.

For instance, should women who carry breast cancer gene mutations have preventive mastectomies? The two types of gene mutations — BRCA1 and BRCA2 — carry different risks.

Another factor which must be considered is whether the cancer is likely to be sensitive to estrogen. Estrogen is the primary female sex hormone.

Still another concern is whether a woman has finished childbearing. Drs. Hartmann and Lindor feel that, if a woman is a BRCA2 carrier, she should wait until age 45 to have her ovaries and fallopian tubes removed. The current recommendation is for removal between age 35 and 40.

Gene testing is now an option for many women, but this can also make decisions more difficult. Researchers said the potential benefits and risks are different for women who have the mutations versus women who only have a family history.

Drs. Hartmann and Lindor recommend further research to determine how women make these difficult decisions, and how the decisions affect them afterward.

“Many of the studies we discuss were published recently, so we are taking advantage of the increased knowledge of the types of cancers that these women develop and the ages at which they occur to suggest how we can change our thinking around their management,” Dr. Hartmann said. “It is part of medicine today to try to individualize recommendations whenever possible.”

This report was published Feb. 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were disclosed.